Summary: The gut microbiome has previously been linked to some neurological and psychological disorders. Now, researchers are investigating whether utilizing microbes from the gut could potentially treat those suffering from depression and other mental health disorders.

Source: UT Southwestern

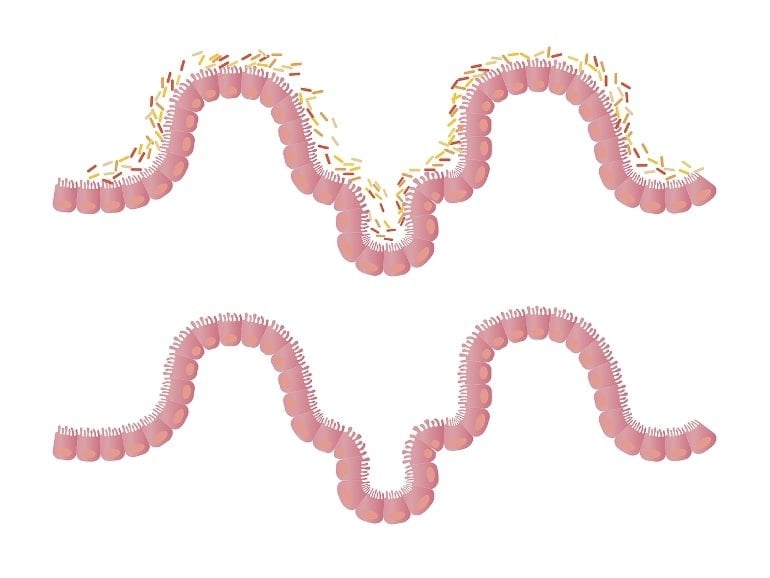

The role of the microbiome in intestinal and systemic health has garnered close attention among researchers for many years.

Now evidence is mounting that this collection of microorganisms in the human gut can also impact a person’s neurological and emotional health, according to a recent perspective article in Science by a UT Southwestern researcher.

Neuroscientist Jane Foster, Ph.D., Professor of Psychiatry at UT Southwestern and a leading expert on the microbiome, outlines how scientists are unraveling the relationship of the microbiome to the brain, including connections to diseases such as depression and amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS).

Dr. Foster, who was the first to link microbes in the guts of mice to anxiety, said animal studies have revealed certain microbes and related metabolites that increase anxiety-like behavior and brain function. Translating these findings to clinical populations could lead to novel therapies to improve symptoms and clinical outcomes.

Dr. Foster joined UT Southwestern and its Center for Depression Research and Clinical Care (CDRC) in May to lead the effort to connect the dots between a person’s 39 trillion gut microbes and their propensity for brain disease. She previously served as Professor at McMaster University in Ontario and co-molecular lead of The Canadian Biomarker Integration Network in Depression (CAN-BIND).

“People who are at risk for depression or diagnosed with depression are heterogeneous. So we want to use biology to understand the biomarkers that can help define the different clusters of people,” Dr. Foster said.

She said UT Southwestern’s approach, which is built on the premise that clinical care and research go hand-in-hand, attracted her to join the center.

“That holistic approach is necessary if we are going to find better answers for people suffering with mental illness,” Dr. Foster said.

The CDRC conducts research in unipolar and bipolar depression to better understand the causes of depression, identify new treatments, and improve existing ones.

“I am very pleased that we were able to recruit Dr. Foster to join our center, given our continuing goal to investigate the biosignature of mental health through a multipronged approach,” said Madhukar H. Trivedi, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Director of the CDRC.

Drs. Foster and Trivedi previously collaborated to look for immune markers in blood samples obtained through CAN-BIND to see how inflammation might influence depression, and in stool samples collected from participants in the longitudinal Texas Resilience Against Depression study.

If the sample from a patient with depression yields certain microbes that are associated with treatment success from certain antidepressants or therapies, this may drive personalized medicine for this patient.

“Currently we have a host of treatment choices, yet decisions are predominantly based on behavior and self-report, and imaging and EEGs in some cases,” Dr. Foster said. “Antidepressants typically work for just around 40% of people. Other choices include cognitive behavioral therapy, deep brain stimulation, or even exercise and diet. By expanding on the individual patient’s profile, can we now improve the number of people that respond to a particular treatment?”

Dr. Trivedi holds the Betty Jo Hay Distinguished Chair in Mental Health, and the Julie K. Hersh Chair for Depression Research and Clinical Care.

Source: https://neurosciencenews.com/gut-microbes-mental-health-21385/